October 29, 2025

Data Shows Endangered Palau Ground Doves Swiftly Recovering After Successful Palauan Island Conservation Effort

Astounding evidence of recovery on Ulong Island in Palau after just one year!

Published on

July 18, 2017

Written by

Sara

Photo credit

Sara

Though seabirds are named and well-known for the ample time they spend in and above the ocean, they also depend on the land, with islands being especially significant. Through migration, foraging, and nesting, seabirds bring sky, island, and sea into relationship. Their ways of life contribute to the health of island plants and wildlife, and in turn, island resources support the survival and diversity of seabird species. Today, these dynamic ecological relationships are vulnerable to a defining environmental crisis of the Anthropocene: invasive species. However, removing invasive species from islands reinstates hope for the threatened birds of the sea. A new scientific study published in the journal Animal Conservation examines the long-term impacts of this form of conservation intervention.

Dynamic and mobile, the birds of the sea connect the ocean’s remote terrestrial ecosystems to a larger ecological network. One can see this connectivity more concretely by tracing the patterns of seabird migration. Though maps of seabirds’ migratory patterns somewhat resemble a five-year old’s art project, these journeys require sophisticated navigation skills. Seabirds draw literal flight-paths of connectivity between land masses and important marine sites.

Many seabird species make remarkable migrations to nest and rear chicks on select islands. Some seabirds return to the same island year after year, a phenomenon known as “philopatry,” meaning “home-loving.” People around the world enjoy a famous example of philopatry in “Wisdom” the Laysan Albatross, the oldest known wild bird. Wisdom spans the open ocean to alight on Midway Atoll to nest with her mate every year.

Seabirds’ natural behaviors are key to functionality and biological diversity on islands and in their surrounding marine habitat. Seabirds bring important marine nutrients to islands, and contribute to habitat for other species. These relationships are subtle to the naked eye, only becoming clearer through scientific observation. But when human impact alters a seabird’s home, natural ways of life can turn deadly. A grim picture unfolds when, after thousands of miles of flight, a seabird pair returns to a home infested with invasive predators.

When human impact alters a seabird’s home, natural ways of life can turn deadly.

Invasive species such as rats and feral cats, introduced to island ecosystems by humans, put seabird colonies at risk. Many seabird species nest on the ground or in burrows, where eggs and chicks might as well be laid on a silver platter for the predatory invasive mammals.

Philopatric seabird species–the ones that return to the same nesting site every year–are faced with a contradictory set of evolutionary impulses: to return home where they expect to meet their mate and nest, and to avoid dangerous predators. Many seabirds are unable to find a suitable nesting site that is free of invasive predators. They have their eggs taken from them time after time. They return to their nests from foraging to find eggs and chicks gone, or worse–being eaten alive. As ecologically sensitive seabird eggs and chicks become rat food, breeding cycles fail and their populations begin to decline. Seabird species once thriving and abundant begin to slip toward extinction–there’s no escaping the predators that were never meant to be there. Left to unfold, the deadly circumstances are liable to get worse. But fortunately, a remedy is available–there is no need to stand by watching helplessly.

Left to unfold, the deadly circumstances are liable to get worse. But fortunately, a remedy is available–there is no need to stand by watching helplessly.

Conservation intervention can and does substantially support seabird species and can even prevent extinction. Teams of scientists, conservationists, civilians, and public officials have demonstrated repeatedly that eradicating invasive species from islands improves conditions for seabirds as well as other native species. While ample research demonstrates the significant conservation gains offered by invasive species removal, no study has explored the long term effects of this form of conservation intervention on seabird populations—until now.

Conservation intervention can and does substantially support seabird species and can even prevent extinction.

Scientists wanted to better understand seabirds’ long-term responses to invasive species removal. For seabirds, many years pass between fledging (leaving the nest) and breeding. Thus the seabird chicks that are saved by predator removal will not contribute much to their species’ population growth at first. This delay means that the payoff of conservation intervention is better measured over many years, after several generations of reproduction can play out.

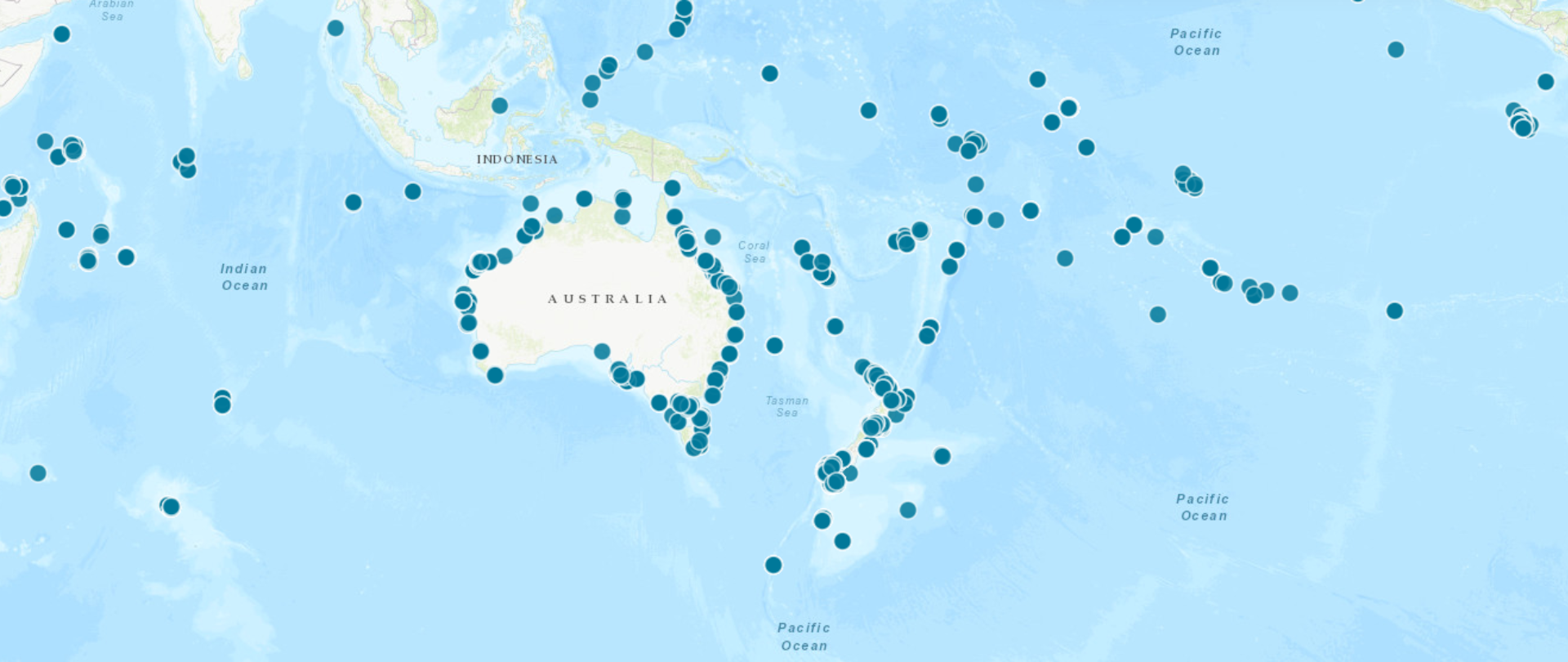

To better understand the process of seabird recovery following invasive species eradication, scientists assembled scattered global data on long term seabird population changes. The study, “Seabird population changes following mammal eradications on islands” examined 61 islands spread across all the world’s major oceans, including islands near and far from the equator, from the warm South Indian Ocean to the frigid seas of the North. The scientists examined 181 seabird populations made up of 69 species and found that different seabird species respond differently to invasive species removal. Additionally, the type of eradication, as well as size and distance from neighboring seabird colonies, influenced seabird recovery.

Removing more than one invasive species from an island was followed by faster population growth than removing just one. More surprising to the scientists was that unexpected seabird species began to colonize islands that had just undergone invasive species removal. This finding suggests that seabirds are less attached to their traditional nesting sites than was previously thought, though some of the unpredicted seabirds were first-timing nesters–young individuals who were choosing a site for the first time and were drawn to predator-fee sites. Dr. Nick Holmes, Island Conservation Director of Science and co-author on the study, commented:

This research reinforces the well-documented benefits of invasive species removal on islands. Just a few years of conservation intervention can make the difference between extinction and recovery for seabirds.

The research suggests that building the cost of long-term monitoring (ten years) into conservation project budgets would help scientists understand how invasive species removal benefits seabirds and inform selection of future restoration sites. Another key finding was that long-term monitoring is important for understanding seabird and ecosystem recovery after invasive species removal.

Restoring island ecosystems by removing invasive species is key for keeping at-risk seabird species safe from the oblivion of extinction. Preventing extinction is undoubtedly valuable for biodiversity and for the seabirds themselves. Beyond that, preventing extinctions of seabirds, important ecological connectors for islands and marine habitats, protects a wide range of plant and animal species. The benefits of seabird conservation extend far, wide, and deep. Seabirds form a foundation for ecological health across oceans and islands.

The benefits of seabird conservation extend far, wide, and deep. Seabirds form a foundation for ecological health across oceans and islands.

As the Anthropocene unfolds, seabirds will serve as important indicators of the health of island and marine ecosystems. Opening the door to conservation and monitoring projects that will support these connectors of land, sea, and sky is a strategic step in the task of caring for the Earth, and for resisting mass extinction.

Featured photo: The Vulnerable Stejneger’s Petrel is threatened by invasive species, including feral cats and rats. Credit: Island Conservation

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

October 29, 2025

Astounding evidence of recovery on Ulong Island in Palau after just one year!

August 28, 2025

A new paper reveals the benefits of holistic restoration on Australia's Lord Howe Island!

May 19, 2025

Read our position paper on The 3rd United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC 3) to see why we're attending and what we aim to accomplish!

March 20, 2025

The DIISE is full of important, publicly-accessible data about projects to remove invasive species from islands all around the world!

December 10, 2024

We're using a cutting-edge new tool to sense and detect animals in remote locations. Find out how!

December 9, 2024

Groundbreaking research has the potential to transform the way we monitor invasive species on islands!

December 4, 2024

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

November 22, 2024

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

November 18, 2024

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

October 3, 2024

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!