February 6, 2026

Planting Native Trees Rejuvenates an Entire Community: An Interview with Solange

¡Mira el video de Solange y lee una entrevista sobre Robinson Crusoe! Watch Solange's video and read an interview about Robinson Crusoe!

Published on

December 22, 2025

Written by

Island Conservation

Photo credit

Island Conservation

“Remote sensing”–it sounds mysterious and high-tech, and when I tell people it’s a huge part of my job, I sometimes get curious looks. At its core, remote sensing describes the act of observing nature from a distance.

Here at Island Conservation, much of our work to holistically restore islands for nature and people happens on islands that are challenging to access—and physically challenging to work on, at that! So, we use remote sensing, including camera traps, satellites, drones, and acoustic monitoring, to understand how islands are changing over time in response to the work we and our partners do.

Before these technologies, our main method for understanding the health of an island ecosystem was to visit once every few years. We would get snapshots, but not the full story. Remote sensing fills that gap by giving us continuous, long-term data.

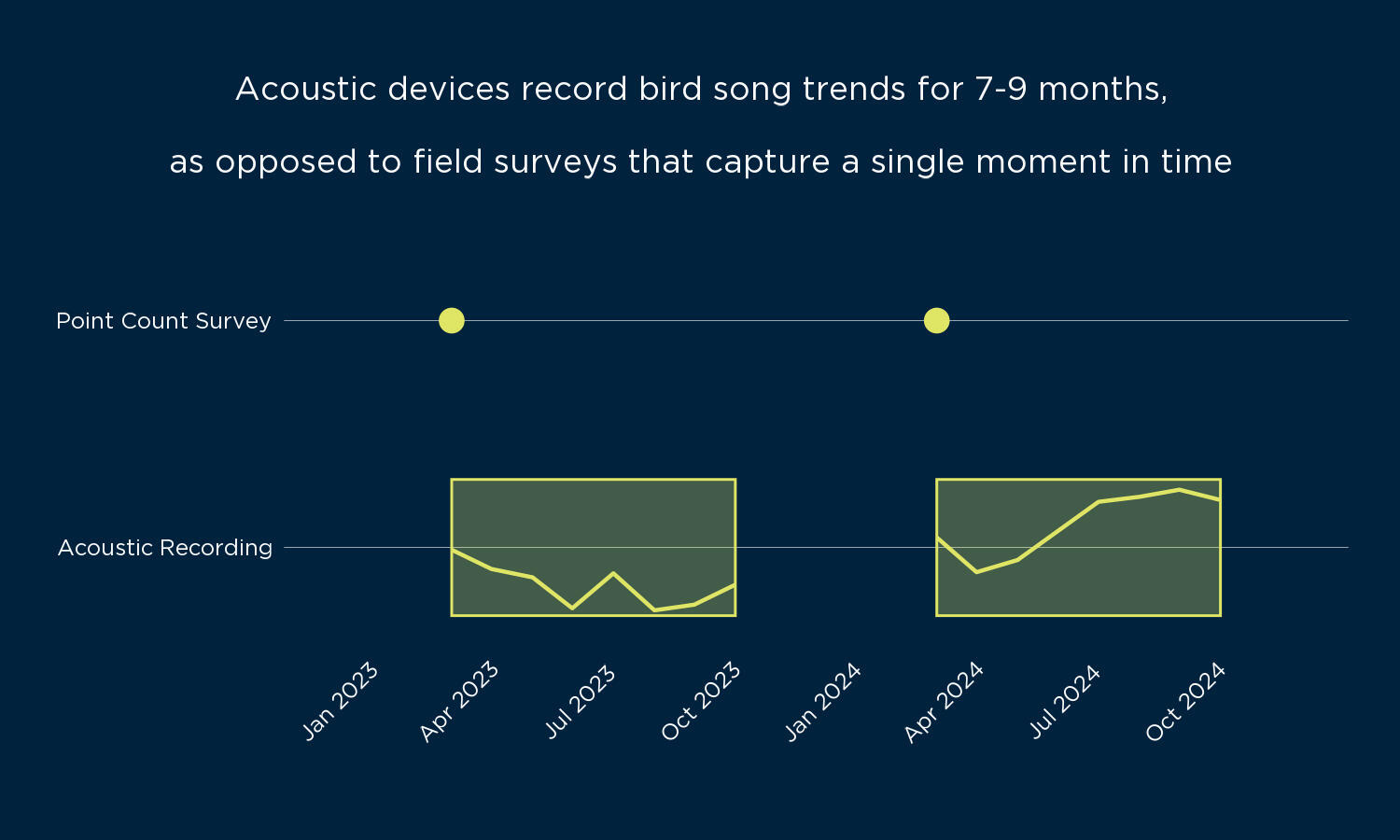

This graph gives an example how much richer our data can become when we use acoustic recordings to measure bird presence, rather than sending individual scientists to do point counts:

From this long-term data, we can gain insight into answering critical questions. Is native vegetation recovering? Are seabirds returning to nest? Are invasive predators present? Which areas need additional action to meet restoration goals? Remote sensing helps guide Island Conservation’s decisions so we can make island recovery happen more efficiently or in new ways

Our toolkit is diverse:

Each tool has its benefits and challenges. Remote islands often lack internet, so we still rely on SD cards instead of cloud uploads. Dense vegetation means batteries instead of solar panels, so we do have to send in real humans to change out SD cards and batteries. And then there’s the sheer volume of data—hundreds of thousands of images and thousands of hours of audio that need to be processed.

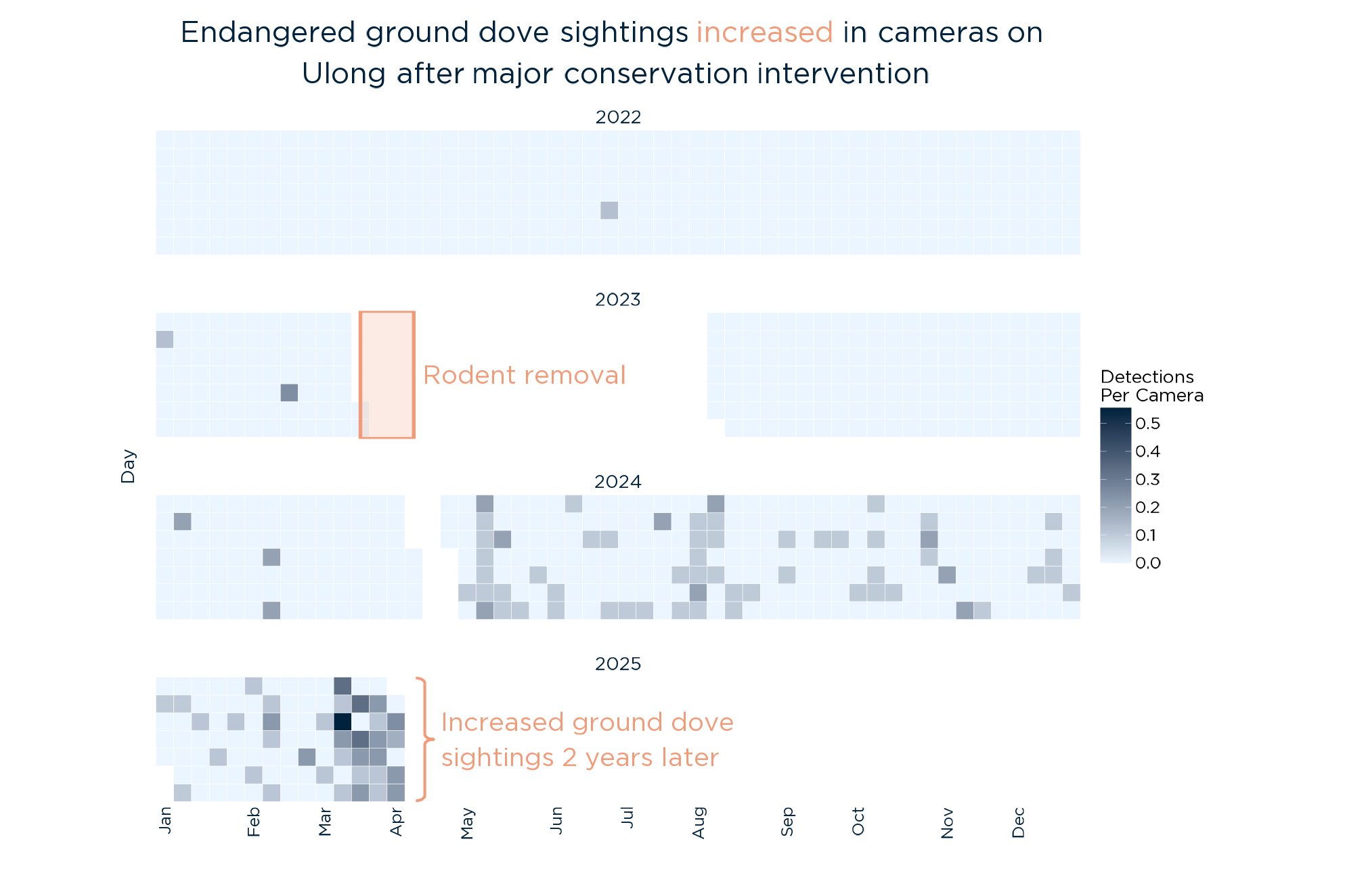

One of my favorite examples of this work in action comes from Ulong Island in Palau. Over three years, we collected 528,310 camera trap images and 14,796 hours of acoustic recordings. That data traveled 6,666 miles from Ulong to our analysis hub in Santa Cruz, California.

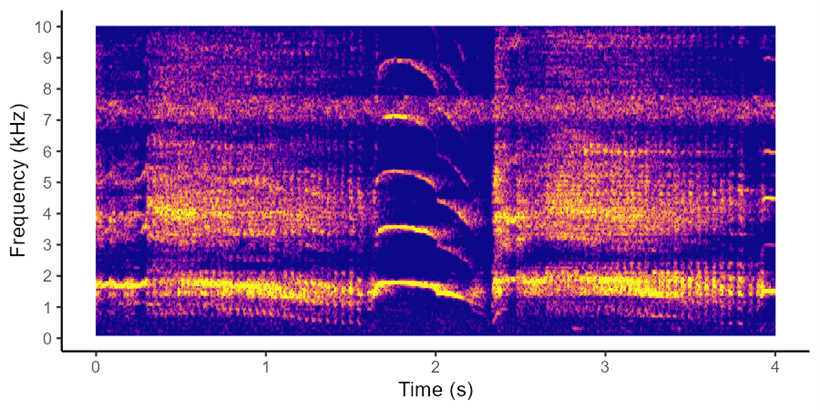

We don’t analyze all this data alone. Partners like Conservation Metrics help us analyze acoustic data using a machine learning technique called a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), which can detect species-specific calls—like the signature haunting cry of Ulong’s Tropical Shearwater—hidden in thousands of hours of recordings.

For satellite imagery, we collaborate with terraPulse and academic partners to process NASA Landsat Earth observation data into metrics that describe vegetation cover, structure, and function, which give valuable landscape-scale insights to field teams. These ‘birds-eye-view’ datasets allow them to identify areas of interest that are difficult to access, saving them time and energy in the field.

Artificial intelligence plays a huge role in making this work possible. Our AI-assisted workflow for processing camera trap imagery uses Megadetector, a computer vision model that flags images likely to contain animals. After the model identifies potential wildlife, our team reviews each flagged image to confirm the species. This human-in-the-loop approach ensures accuracy while saving countless hours of manual sorting.

All of this effort—AI models, acoustic sensors, satellite imagery—feeds one overarching goal: reproducible science. By using standardized methods and transparent workflows, we make sure that our findings can be verified, repeated, and built upon. These tools allow us to provide meaningful evidence of the outcomes that can be realized through conservation action on islands.

Island Conservation prides itself on being a leader in conservation science. We’re always piloting new tools and methods to gather data, but it’s the stories that the data tells that make it valuable. And time and time again, it shows that holistic restoration on islands yields outsized benefits for nature and people. I’m glad to be part of a data journey that results in more resilient and biodiverse island ecosystems!

There’s more than one way to make an impact. Join our collective of dedicated supporters by donating today or signing up for our newsletter to stay informed.

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

February 6, 2026

¡Mira el video de Solange y lee una entrevista sobre Robinson Crusoe! Watch Solange's video and read an interview about Robinson Crusoe!

January 22, 2026

Our Senior Director of Impact & Innovation, David Will, explains the importance of the Circular Seabird Economy for nutrient transfer!

January 15, 2026

Not all Marine Protected Areas are equally effective. A new study shows how high-quality, well-implemented MPAs provide outsized impacts for biodiversity!

December 4, 2025

A new study reveals how seabirds, connector species between land and sea, play a huge role in the health of coral reefs!

November 25, 2025

A new scientific paper is changing the way we understand Rapa Nui (Easter Island)'s ecological history!

November 21, 2025

Holistic restoration is at work on Floreana Island, where the largest conservation project in the history of the Galápagos is underway!

October 30, 2025

Our proposal for a United Nations-sanctioned Decade of Island Resilience spotlights the power of global small islands!

October 26, 2025

A new study shows the power of seabirds to drive entire ecosystems by circulating nutrients between land and sea!

September 12, 2025

How can you make the maximum impact on the planet with your donation? Some conservation actions are most cost-effective than others!