October 29, 2025

Data Shows Endangered Palau Ground Doves Swiftly Recovering After Successful Palauan Island Conservation Effort

Astounding evidence of recovery on Ulong Island in Palau after just one year!

Published on

July 21, 2017

Written by

Emily Heber

Photo credit

Emily Heber

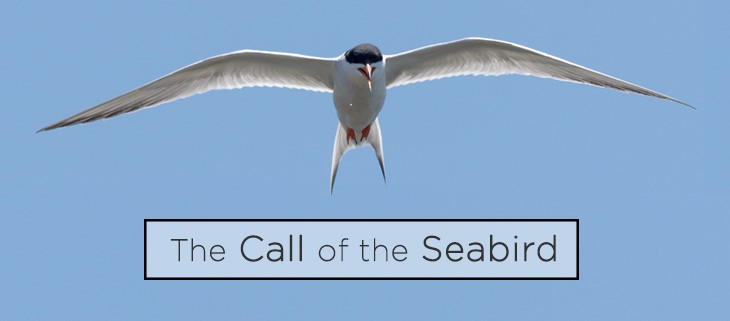

In South Bay San Francisco, California, a Forster’s Tern (Sterna forsteri) flies overhead and lets out a call to its colony below. This “advertisement call” is almost the bird’s way of saying “hello” to the colony on the island. Researchers have found that acoustic monitoring and analysis of these calls can reveal quite a bit about the seabird population on an island.

In order to count seabirds, researchers often use extensive labor and specialists to locate elusive species hiding on remote portions of islands. Now, Abe Borker, a Seabird Biologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz is trying to change that and make population studies of seabirds more cost-effective and efficient. Borker explains that based on the call of some species of seabirds, you can estimate their population size:

There is a consistent relationship between the number of times the Tern says hello and the number of Terns that are breeding on the island.

Seabirds spend much of their time on land hidden in crevices along steep cliffs, which makes it difficult for researchers to gather population data. Developments in acoustic monitoring offer conservationists a greater understanding of a population before and after conservation efforts. Creating a new method to evaluate the success of invasive species removal projects and can help save threatened seabirds.

In order to study the audio recording, Borker uses a computer program. The program helps to distinguish between bird calls and background noises of the island. Currently some tweaks are still necessary before acoustic monitoring can give researchers accurate data on populations, but Borker is hopeful that once completed, the acoustic monitoring and analysis will be more efficient than manual counts. David Mellinger, an Oregon State bioacoustician explained that acoustic monitoring could even help with accuracy:

If you are sitting there for hours [counting birds] your attention tends to wander. A computer it is more consistent. Computers don’t get bored.

Acoustic monitoring for seabirds calls is not a new idea. Island Conservation used audio recordings on Hawadax Island, Alaska, formerly known as Rat Island, to monitor for calls of the elusive Leach’s Storm-petrel after removal of invasive species. The recordings found that the birds were returning thanks to the removed threat of predation by invasive rats. Borker’s important work is developing at a critical time for conservation; his efforts will build upon the currently available technology and enhance conservation efforts for seabirds.

Featured Photo: Forster’s Tern flying. Credit: Lee Jaffe

Read the original study: Wiley Online Library

Source: Inside Science

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

October 29, 2025

Astounding evidence of recovery on Ulong Island in Palau after just one year!

June 13, 2025

Our partner Conservation X Labs has joined the IOCC, committing to deploying transformative technology to protect island ecosystems!

May 19, 2025

Read our position paper on The 3rd United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC 3) to see why we're attending and what we aim to accomplish!

December 4, 2024

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

November 22, 2024

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

November 18, 2024

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

October 3, 2024

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

September 10, 2024

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

September 5, 2024

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

December 14, 2023

Join us in celebrating the most amazing sights from around the world by checking out these fantastic conservation photos!