October 29, 2025

Data Shows Endangered Palau Ground Doves Swiftly Recovering After Successful Palauan Island Conservation Effort

Astounding evidence of recovery on Ulong Island in Palau after just one year!

Published on

August 20, 2019

Written by

Wieteke Holthuijzen

Photo credit

Wieteke Holthuijzen

One of the wonders of the wide Pacific Ocean is that of a Laysan Albatross / Mōlī gliding across the waves and wind, seemingly without effort. They are made for a life at sea—and indeed, they spend the majority of their lives soaring throughout the North Pacific, upwards of 90% of their entire lifetime in the sky and at sea. They cover extensive tracts, sometimes hundreds of miles a day, way out west to Japan, north to the Aleutian Islands, or even eastwards to California in search of food.

Built for a life at sea, albatross have very long, narrow wings which help them to glide easily through the air. The particular kind of gliding is called “dynamic soaring,” in which the albatross use the small amount of wind produced by waves at sea in order to power their flight. Out in the North Pacific, albatross are often found gliding just above the surface of the water, without flapping at all. Albatross also use a kind of flight called “slope soaring,” in which they glide up the wind deflected upwards from a wave. Together, albatross use these two methods of flying out at sea and it creates quite a beautiful scene; one moment, an albatross is gliding just above the seawater and the next, it is soaring upwards into the sky—all without flapping. In fact, albatross have a special anatomical feature in their shoulder that essentially locks their wings in place; this “shoulder locking” mechanism allows albatross to keep their wings open without using any muscles, thereby decreasing the amount of effort it takes for the albatross to fly far.

However, with such broad wings, take-off (and landing) can be difficult, because albatross need a crucial amount of speed in order to become airborne. They usually need a runway of sorts, running as quickly as possible, flapping their wings as fast as they can, and then eventually taking off (similar to an airplane). Landings can be equally difficult, especially in birds that have been at sea for months, or in light winds. In the absence of the braking effort of a strong wind, landing birds may occasionally tumble on landing.

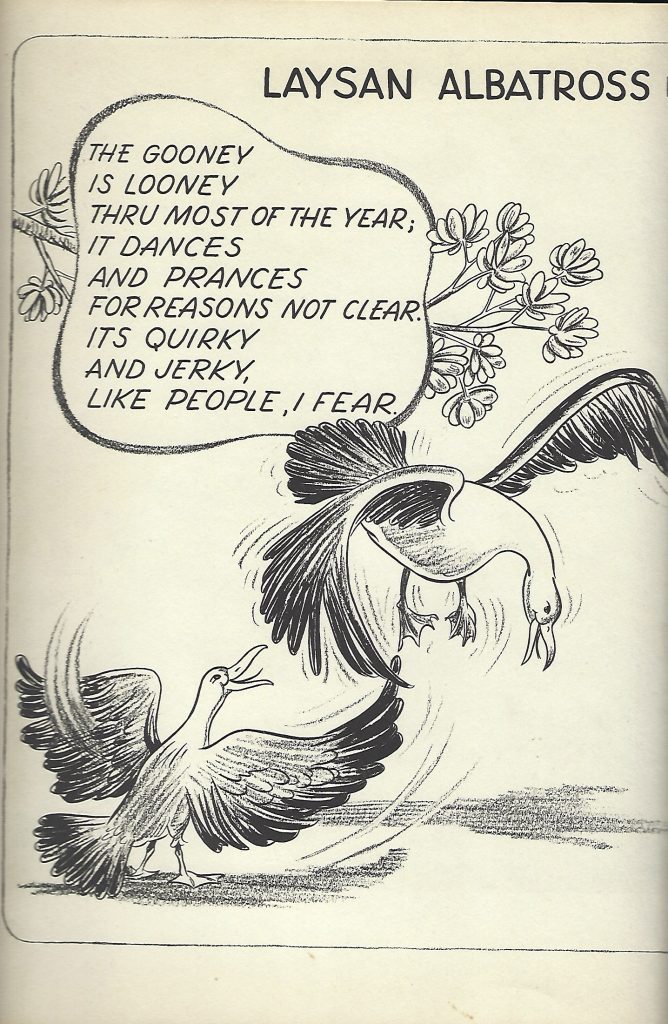

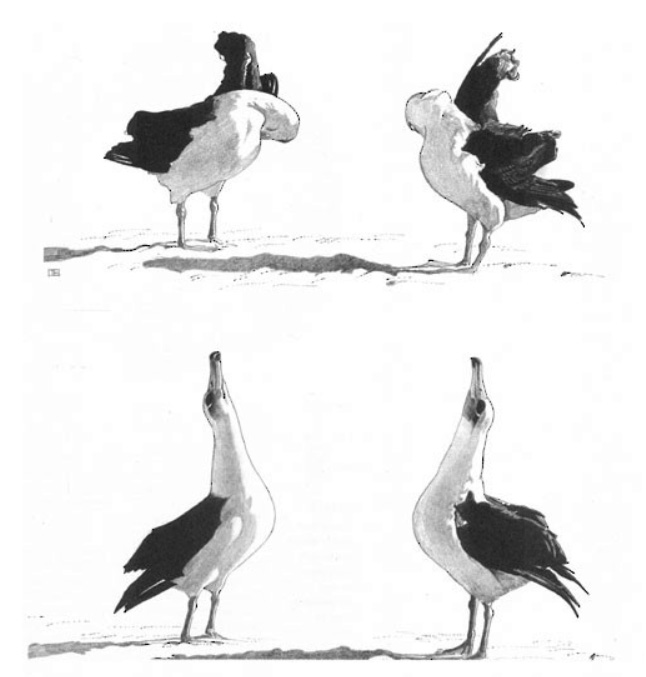

Nearly every year, about 70% of the world’s Laysan Albatross trace their long, marine routes back to Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge to breed. Albatross display incredible site fidelity (or philopatry)—meaning that they nest in the same area (within a few meters) whenever they breed. The act of finding and attracting a mate is perhaps one of the most unique and adored aspects of albatross. Laysan Albatross complete a very complicated and loud courtship “dance” with one another with several kinds of special movements, like bill claps, sky moo’s, and scapular action. It can take years to get this unique albatross courtship display just right. Younger albatross may dance with many different individuals (and learning the courtship takes practice) but in time, the birds may find a mate and start to breed.

Albatross are textbook seabirds; they are large, long-living (Wisdom, the world’s oldest wild bird is more than 68 years old), display delayed sexual maturity (they may breed at age 5 at the earliest), breed in colonies, have long-term pair bonds (i.e., “mate for life”), and lay only one egg per year. Usually, the female albatross will begin construction of a nest, 1 to 3 days before she lays her egg. Females only lay 1 egg each year; if something happens to the egg, the albatross will unfortunately not lay another one. Typically, it takes about 65 days for an albatross egg to hatch! Male and female albatross will take turns incubating the egg, sitting on the egg for about 2 weeks at a time, and then switching out so the other parent can go to sea and forage. After the chick hatches, both parents will brood the chick for the first few days after hatching. Then, as the chick grows larger, the parents will start to guard the chick, usually up to 2-4 weeks after the chick hatches. By that point, the chick is large and strong enough that it can be safe by itself; more importantly, the chick will be able to thermoregulate, so albatross parents will no longer guard the chick and instead take turns flying out to see, finding food, and bringing it back to their growing (and ever-hungry) chick!

Although Laysan Albatross are numerous, they encounter a myriad of challenges via longline fishing, plastic trash in the ocean, and predation by dogs, rats, and cats. Now, Midway’s albatross face a new threat—invasive, predatory mice. Island Conservation and our partners are going to remove them in July 2021 and restore the balance on the Atoll.

Featured photo: A Laysan Albatross up-close. Credit: Wes Jolley/Island Conservation

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

October 29, 2025

Astounding evidence of recovery on Ulong Island in Palau after just one year!

May 19, 2025

Read our position paper on The 3rd United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC 3) to see why we're attending and what we aim to accomplish!

December 4, 2024

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

November 22, 2024

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

November 18, 2024

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

October 3, 2024

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

September 10, 2024

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

September 5, 2024

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

December 14, 2023

Join us in celebrating the most amazing sights from around the world by checking out these fantastic conservation photos!

November 28, 2023

Rare will support the effort to restore island-ocean ecosystems by engaging the Coastal 500 network of local leaders in safeguarding biodiversity (Arlington, VA, USA) Today, international conservation organization Rare announced it has joined the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge (IOCC), a global effort to…