October 29, 2025

Data Shows Endangered Palau Ground Doves Swiftly Recovering After Successful Palauan Island Conservation Effort

Astounding evidence of recovery on Ulong Island in Palau after just one year!

Published on

January 27, 2017

Written by

Sara

Photo credit

Sara

Once biodiversity is lost, can it be recovered? A paper published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, “Recent Extinctions Disturb Path to Equilibrium Diversity in Caribbean Bats,” by Luis Valente, Rampal S. Etienne, and Liliana M. Dávalos offers helpful new insight into this complex question. The researchers turned to islands to better understand the consequences of biodiversity loss.

The study is based on the Island Equilibrium Theory of Biogeography, first introduced by Robert MacArthur of Princeton University and E.O. Wilson of Harvard. According to this theory, there is a relationship between the number of species that travel to an island and species on the island going extinct. The rate at which species populate and go extinct from an island depends on the type, size, and location of the island.

Most islands start out with no species present but may be colonized over time. Species swim or fly to the island, and over time some of these species can undergo adaptive radiation–that is, branching out into more species (such as the Darwin’s finches did in the Galápagos). The theory states that the number of species on oceanic islands gradually increases until it reaches a diversity steady state, with no significant additions or losses. Scientists call this the dynamic equilibrium value.

The greater Antilles, (including Cuba, Jamaica, Puerto Rico and Hispaniola) from which the researchers took samples from, are hotspots of island species diversity (home to many adaptive radiations – including the famous Anolis lizards). However, until now, scientists did not know whether these ecologically important islands were at equilibrium or not.

Usually, the larger the island and the nearer the mainland, the higher the number of species present once equilibrium is reached. Biodiversity is the key to ecosystem resilience. Ecosystems with a wide variety of species have higher resistance to stressors, such as disease or climate change, than ecosystems with low biodiversity.

The scientists examined samples from a fossil record of bats native to the Greater Antilles Islands of the Caribbean. The specimens included existing and extinct species. By examining the fossil record, the scientists were able to confirm that the bats had reached equilibrium diversity. This stable point was disturbed however, after humans colonized the Greater Antilles. Almost a third of island lineages disappeared, constituting a sharp downturn for bat diversity.

These losses brought the number of bat species below their once-stable equilibrium value. The scientists performed calculations to answer a nerve-wracking question: How long would it take for nature to undo the damage humans had brought on?

The researchers calculated that it would take eight million years for nature to recover the lost biodiversity of Caribbean bats. While the bats were able to survive dramatic changes in climate, including glacial conditions, they are proving far less able to persist through anthropogenic (human) impacts. You may wonder how humans can so drastically affect these island bats. Some of the forces that put strain on these bats and other island wildlife include invasive species, habitat destruction, and natural resource exploitation. The paper states:

Insular species have evolved in isolation and have proved vulnerable to both Pleistocene climate change and human activities, including the introduction of non-native species, habitat destruction and exploitation…Over a third of (Caribbean bat) species and nearly a third of lineages went extinct from the (Greater Antilles) islands, probably as a consequence of human colonization.

Human activities have made it impossible for the ecosystem to sustain the equilibrium diversity value for Caribbean bats. Co-author Dr. Luis Valente commented:

This study raises awareness for conservation of the unique bat species of the Caribbean that may have been overlooked by policy-makers.

The extinction flare is becoming more and more difficult to ignore. The news regularly reports growing concern for endangered species, warning us that animals around the world–with island species particularly at-risk–will disappear forever if we do not take action to protect them.

Not only does biodiversity make nature tick, but it is also what makes our planet so beautiful and interesting. As the 6th mass extinction unfolds around us, it is more important than ever to understand the value of biodiversity, and to find out what it takes to restore it. This study can serve as a template for further research into equilibrium diversity disturbances for a variety of regions and species. It also serves as a clear warning of the long-term consequences of biodiversity loss. Co-author Dr. Liliana Dávalos noted:

Some people argue that if we leave nature ‘alone’ it will quickly return its original state. However, the finding that it would take 8 million years to recover lost diversity suggests that is clearly not the case.

Organizations around the world are working hard to halt the erosion of biodiversity, including us here at Island Conservation. There is rarely a short-term action that has long-term benefits in conservation, but we’ve found one: invasive species removal. Invasive species are the leading cause of extinctions on islands around the world. By removing invasive species from islands, we can prevent extinctions and preserve biodiversity. It’s hard work, but it’s eight million times better than waiting around for nature’s self-corrective processes.

Featured photo: Bat Colony in the Bahamas. Credit: James St. John

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

October 29, 2025

Astounding evidence of recovery on Ulong Island in Palau after just one year!

August 28, 2025

A new paper reveals the benefits of holistic restoration on Australia's Lord Howe Island!

May 19, 2025

Read our position paper on The 3rd United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC 3) to see why we're attending and what we aim to accomplish!

March 20, 2025

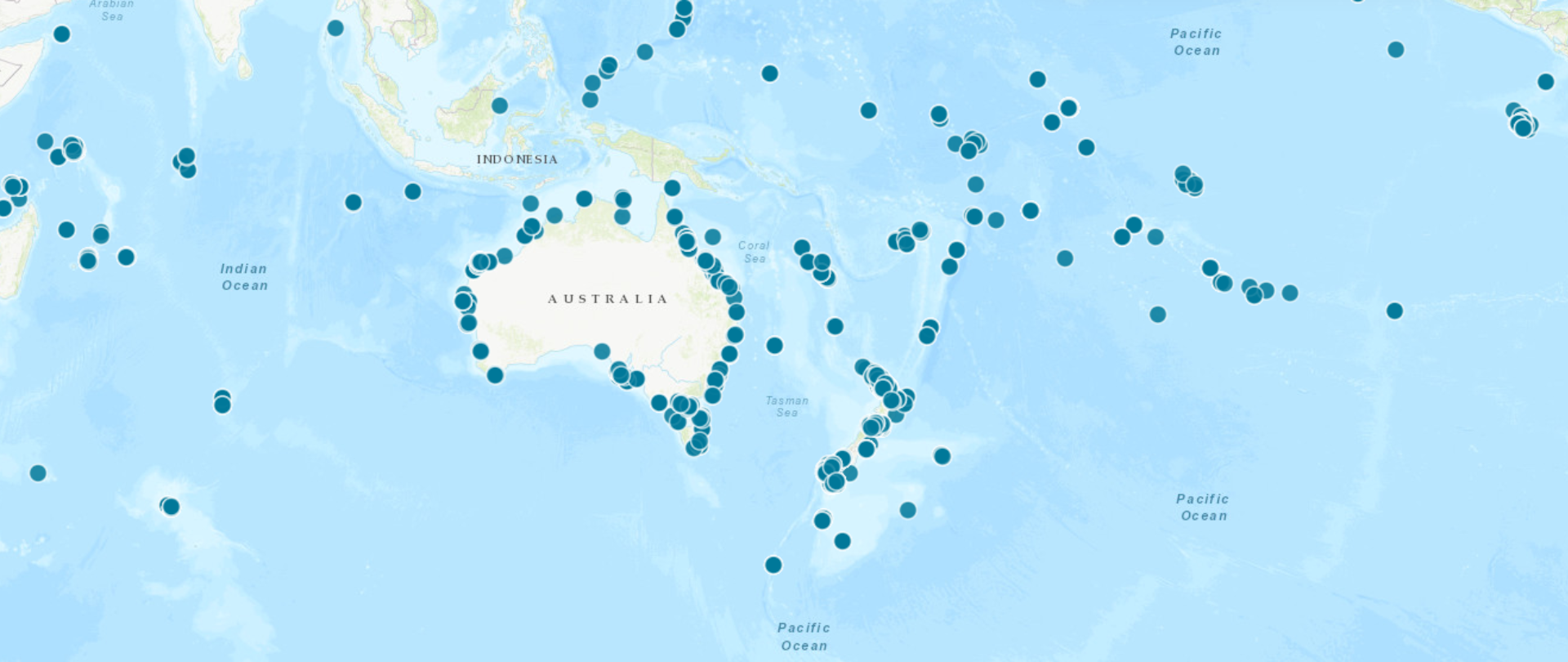

The DIISE is full of important, publicly-accessible data about projects to remove invasive species from islands all around the world!

December 10, 2024

We're using a cutting-edge new tool to sense and detect animals in remote locations. Find out how!

December 9, 2024

Groundbreaking research has the potential to transform the way we monitor invasive species on islands!

December 4, 2024

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

November 22, 2024

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

November 18, 2024

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

October 3, 2024

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!